Make Gibbons Laugh #75

The third edition of “What Are The Right Fuckin’ Books, Will?” !

As always, these are books not that you *should* read but books that “blew my hair back,” to quote that MIT janitor:

Essays That Blew My Hair Back:

Get Me Through The Next 5 Minutes: Odes To Being Alive—James Parker (2024). If Ross Gay had a British cousin, who wrote (wonderfully-short, nutrient-rich) essayettes and “odes to being alive” as opposed to Gay’s famous daily delights, that cousin would sound awfully like James Parker: joy-full, awe-full, sarcastic, tender, witty, “spiritual and salty.” Odes to balloons. Cold showers. Hugs. The nature of self, as seen through Jason Bourne. Constipation. His dog’s balls. The odes are “short exercises in gratitude. Or in attention, which may in the end be the same thing.” (!!)

It’s probably my favorite book I read all year from maybe my favorite prose stylist working today (you can read his column for The Atlantic where these odes began)—gems like these on every page, here describing playing in a band:

“We sound like Neil Young falling out of bed… the more seriously you take it the more fun it is. So with life, so with being in a band. An earnest commitment at ground level gets you access to higher playfulness…we blend, mingle, lose our outlines.”

Dark Days: Fugitive Essays—Roger Reeves (2023). While we’re on literary extended family members, this collection felt like a close relative of Hanif Abdurraqib (also a brilliant poet also writing stunning essays and cultural criticism without compromising their lyricism, dancing freely—but still always on beat, regardless of the song—between the first person, and all its subtle, inspired varieties, and the close third)—that or the grand-nephew of Louise Glück and James Baldwin. My favorite essay: “Beyond the Report of Beauty,” on dancing, its beauty, the dancing of and by and for the dead, and the late, great Michael Williams aka Omar Little.

Poetry That Blew My Hair Back:

You Are Here: Poetry In The Natural World—edited and introduced by Ada Limón (2024). The great Ada Limón (current US poet laureate, author of books I love like The Hurting Kind and Bright Dead Things) curated this collection of (85%) previously unpublished poems from 50 poets—including everyone from Joy Harjo to Ilya Kaminsky (who writes one of the most thrillingly minimalist poems I’ve ever read and is becoming one of my absolute favorite poets).

As the front flap suggests, “each poem engages with its author’s local landscape—be it the breathtaking variety of flora in a national park, or a lone tree flowering persistently by a bus stop—offering an intimate model of how we relate to the world around us and a beautifully diverse range of voices from across the the United States.” The poems are certainly *about* nature. But to me, their work seemed more concerned with the first half of the title than the second half: affirming, grounding, rooting, us and them, and you, in direct address, in place, here, with intimacy, and care, without needing any direct objects or prepositions. Presence, awareness, and clarity occasioned by nature.

Alberto Ríos enchanted me with backyard spiders. Camille Dungy enchanted me with clouds. Ilya Kaminsky enchanted me with rain.

Break the Glass—Jean Valentine (2010). Jean Valentine is probably one of your favorite poets’ favorite poets. When I read her work, I’m reminded of William Carlos Williams’ lines: “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.”

What I’ve “found there,” in her poems, are, yes, some of my favorite things that don’t usually make the news: obscure animals, secular spirituality, exploring heavy things with acuity yet restraint. I’ve found someone enlivened by poetry’s imaginative leaps and its line-breaks that, in her hands, serve as a profound reminder beyond the page: to truly inhabit this, here, just this, whatever this is, with acceptance and trust, before assuming what’s next, before scanning for what’s next. What I’ve always “found there,” in her poems, is a rare blend of dream-like surrealism and Emily Dickinson-quality minimalism.

(Also, utterly delightful that she was the poet-in-residence of Ross Gay’s community orchard in Bloomington, Indiana in her 80s before she passed.)

City of Coughing and Dead Radiators—Martín Espada (1993). Espada is a breathtaking poet in his own right. But throughout this, I kept thinking of other New York artists who might as well live in Espada’s creative family tree: Alice Neel (really seeing and loving the unseen among her neighbors), Audre Lorde (in her decolonizing strength), James McBride (in his attention towards the gritty and mundane).

“Political poetry at its best,” reads a blurb. “...gives dignity to the insulted and the injured of the earth.”

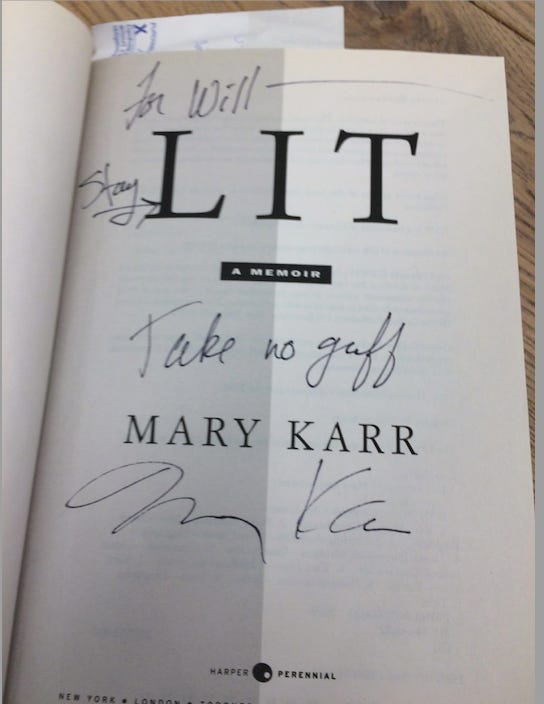

Tropic of Squalor—Mary Karr (2018). If you’ve followed these book reviews over the years, you’re probably familiar with my nervous, bumbling encounter meeting Mary Karr when she gave a reading at Emerson for Tropic of Squalor then did a book signing.

I’d long been a huge fan (her famous commencement speech, her episode of On Being, The Liar’s Club and Lit). I brought my copy of Lit. I was wearing a sweatshirt that read HARRY across the sleeve (as in Styles). She asked if that was my name.

“NoUHHH. TheeeeeeeAH. ehYEAHwellWill-uh. WillWILL...Is. UMhaHA. It’s…yeah.”

She graciously took in my bumbling.

“Will! That’s always been my favorite name.”

I’m sure she sensed I could use this inscription slash reminder slash mantra (couldn’t we all?):

I finally got to Tropic of Squalor, and it’s Mary Karr at her best: elegant but dry. Sassy with a scalpel but still soulful. Sentences, in both prose and verse, that resemble magic tricks: sleight of hand that folds me over in its turns and precision. (The power of Mary Karr: she writes a poem about playing basketball as a patient at McLean’s, decades ago, a poem which is unsurprisingly incandescent in her hands, but it’s the dedication itself that’ll first shoot lightning across your horizon. Other gems: downpours in Manhattan, pretentious dinner parties, wandering post-9/11 rubble with buddy George Saunders).

Stay lit. Take no guff.

Memoir That Blew My Hair Back:

Grief Is for People—Sloane Crosley (2024). The two things I most seek out/savor/delight in as a reader, regardless of subject, plot, tone, form, anything: 1. grace, care, and joy with language and 2. authentic feeling in an engaging voice (i.e. voice). You know who has an indelibly cheeky-yet-trusty voice? Razor-sharp wit and snark but also vulnerable and intimate without ever feeling jarring? You know who writes some of the most polished, elemental sentences? The great Sloane Crosley, whose essay collections and novels feel like Nora Ephron crossed with Nick Hornby. But here, it’s like she wrote the funnier, cheekier sequel to Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking. (A third thing I really seek out/savor/delight in: work that’s writing toward clarity not from clarity, with urgency, discovering in real time. E.g. ^^^).

Spiritual Books That Blew My Hair Back:

The Seven Generations and The Seven Grandfather Teachings—James Vukelich Kaagegaabaw (2023). Come for the timeless Ojibwe wisdom and spirituality, the Native American respect for nature and each other, lessons on interconnection, humility, and inner harmony. Stay for the Ojibwe linguistic tutorials (E.g. six out of every seven words are verbs (!), language with such nuance, malleability, and ecological roots, so to speak).

Novels That Blew My Hair Back:

James—Percival Everett (2024). The elevator pitch: the great Percival Everett wrote a much-overdue redux to Huck Finn from Jim’s first-person perspective. It’s an essential reimagining, obviously, but also, in its own right, brilliantly paced and a brilliant meditation on language, expression, and code-switching. And, per Kiese Laymon’s blurb, a reminder that “Percival Everett is a genre.” (i.e. his own subgenre of satire: huge-hearted but restrained, biting but never bitter).

Housekeeping—Marilynne Robinson (1980). I first read this in 2018 and loved it. Loved how it dealt with profound (almost biblical) loss and upheaval with such lightness—not as in levity but a light touch, light on its feet, not diminishing or downplaying grief but making its weight somehow almost, paradoxically, light to hold. Depending on your perspective, Housekeeping can feel like folklore or a lucid dream. Loved its language, the most genuinely fresh metaphors while still being grounded in scene (does anyone write interiority this beautifully while also this efficiently? Maybe Virginia Woolf with a stopwatch?).

I re-read this last summer. Very few contemporary novels break open my heart and blow back my hair to this degree. I’m not sure any contemporary novel forces me to slow down my reading this much (independent of its wonderfully puttering plot) in order to savor its language, its wisdom, its non-judgemental attention toward everything.

The misconception with art that’s deemed a “slow burn” (often used dismissively, as if narrative speed is the only reason we consume art!): from the right distance, that glow is never not keeping you warm and never not providing light.

Nobody Is Ever Missing—Catherine Lacey (2014). Your mileage may vary with the hazy plotting or the tight (very insular!) first-person narration. But holy shit: 1. the perceptiveness and existential wit, an endlessly-compelling mind at play, ruminating, leaping, circling, cycling and recycling, rehearsing and grieving, in bites and gulps and fits and starts, 2. the actual turns of phrase that often made me keel over (like Michael Scott at Beach Games, I’m sure there’s a conversion chart somewhere for this scoring rubric: single and double “!”s in the margins, passages underlined, underlines enveloped by circles, underlines with circles and double “!”s in the margins), and 3. a story so admirably quiet and combustive. Like a modern On The Road, in New Zealand, with higher stakes.

Journalism That Blew My Hair Back:

Boom Town—Sam Anderson (2018). It’s 430 pages but reads like you’re careening downhill on a skateboard: I don’t think I’ve ever read a longform journalist who writes with this level of gusto, joy, and humor. For a couple weeks there in April, I’d wake up earlier than usual, without any alarm, giddy to start reading again. Boom Town blew back my literary frosted tips not unlike how the gusts of Oklahoma (featured in Boom Town) took its prairies in flight.

What’s Boom Town even about? I’ll start by simply copying and pasting the subtitle:

Boom Town: The Fantastical Saga Of Oklahoma City, Its Chaotic Founding, Its Apocalyptic Weather, Its Purloined Basketball Team, And The Dream Of Becoming A World-Class Metropolis.

I’ll now copy and paste a section from its Notes On Sources:

“On my first flight out to OKC, I stumbled across the following sentence about the origin of Oklahoma’s violent weather: ‘the state is situated in a zone where three climatic regions—humid, sub-humid, and semiarid—meet and mingle.’ My mind made a little leap; in the margin I wrote, Westbrook, Harden, Durant.”

And now, I’ll copy and paste the book’s very first sentence: “Red Kelly was the man who killed the man who killed Jesse James.”

P.S. Both of Conan’s parents passed away recently (within three days of each other! In the same room! Their bedroom for the last 62 years!). I’ve heard Conan talk about them for years, but it wasn’t until I read their obits that I learned: 1. his dad was med school classmates with both my mom’s parents, who all graduated together 71 years ago, back when there were only 104 people in their class (100 men, four women…). So, it delights me picturing a young (20-year-old!) June Murray and a young Richard Senghas doing bits, in lab coats, with Dr. O’Brien. Conan, Sona, and Matt in the Team Coco podcast studio. Thomas, June, and Dick in the hallways on Longwood Ave. Trios of silly anarchy. Bits and quips. Riffs and gags (and by “bits,” I mean discussing antimicrobial resistance. And by “silly anarchy,” I mean meeting one another in class next to a cadaver—which is how June and Dick actually met.).

And 2. his mom, like my grandma, was a real pioneer in a male-dominated field. Resilient. Gracious. Seemingly incapable of sweating the small stuff, I’ve gathered. Dry sense of humor. Reaching back down the ladder to lift others. All the while, both were moms to six/seven. Big Irish/Scottish Catholic families in Boston. Born at the beginning of The Depression. Teenagers during WW2. Had to grow up QUICKLY.

Very moving, his parents’ story. Very moving, hearing Sona and Matt talk about Conan’s family with the boss out of office. I’ve since been thinking of June in January, ancestors, and how miraculous it is any of us end up here.

P.P.S. Thinking of LA. The sheer loss. The homebound people. All the folks I got to know through Meals On Wheels. The (six!) friendly, widowed, old ladies puttering with their little dogs down San Vicente (including “Magic Johnson,” first and last name every time, Eleanor’s 12-year-old maltipoo). My 102-year-old neighbor, Thelda, who moved into our building in 1957. Who did her daily walking exercises while smiling at—and pointing to—all the flowers. Who, every time I saw her, glowingly told me about her hometown Brooklyn Dodgers. Families watching the sunset from Palisades Park. That cheerful dude who was always at Temescal Canyon, always singing while hiking. The wonderful (treehouse-like!) Little Free Library in Santa Monica Canyon. The old horse stables at Will Rogers. The Coast Live Oaks in Eaton Canyon, Altadena. The Coast Live Oaks off the PCH. The basketball court hiding among the Eucalyptus and Redwoods in Rustic Canyon. Seeing that RED map already covering or quickly approaching all that…😢 To quote Santa Monica transplant, George Saunders: “if you’re a praying person, say a few for Los Angeles and for all victims of dislocation everywhere in the world.”